By: Alex Younevitch, S&P Global Platts

It is not uncommon for people in various commodity industries to believe that their markets exist in some kind of a happy bubble, where only the obvious supply and demand forces or targeted regulations can make or ruin their day. This often goes for the world of coal too.

Shipping is a perfect example of a factor which sometimes gets overlooked. This is evident from industry events these days, where shipping is often either deep down on the agenda or is completely absent from it.

The issue here is not ignorance, of course. When it comes to seaborne coal cargoes, any trader worth his salt would still look at the freight element as it affects the CIF price and delivery time of the product.

The real problem is that freight rates have been depressed and often lacking volatility for years due to a persisting oversupply of vessels. With freight at the bottom, the existing arbitrages settled safely and shipping, while always there naturally, was no longer perceived to be a crucial factor in opening or closing trade routes.

However, the times are changing again. In addition to freight already being on a path for recovery amid rising demand, there is an upcoming disruptive regulation from the International Maritime Organization that is likely to shake up the whole playground.

The global sulfur cap of 0.5% on marine fuels that that will come into effect on January 1, 2020 is already seen as a perfect storm by the oil and shipping industries as it may bring extreme volatility in bunker prices.

The most likely outcome is a sharp spike in costs for shipowners. And as happens in any business, these costs shall be passed along to the customers. For anyone involved in seaborne coal trade, this would mean dealing with a dramatic, long-term increase in freight rates.

The new sulphur cap of 0.5% is a sharp drop from the current limit of 3.5% and in simple terms it means that come January 2020, all vessels around the globe will have to burn cleaner and more expensive fuels or take other costly measures in order to comply.

One way that shipowners could go is using special fuel oil blends, which would fall below the 0.5% cap. However, experts are doubtful that the global refining industry will be able to supply such blends in sufficient volume and variety in time for 2020.

Otherwise the industry could go straight to burning Marine gasoil or MGO, which many expect will be the most popular scenario, at least at first. And while MGO is compliant and more readily available, it also much more expensive than conventional IFO 380 bunkers.

Of course, there are a few alternatives available to shipowners, like LNG bunkering or exhaust control systems, also known as scrubbers. However, both have serious drawbacks.

For example, it takes $3-6 million to install a scrubber on a dry bulk vessel, with costs varying depending on the size of the ship and the type of the scrubber. Retrofitting a 5-10 year old ship, considering current vessels prices, would therefore be prohibitively expensive.

It is even harder to justify LNG as the global bunkering solution as the infrastructure required to support it is not there yet and the upfront costs for retrofitting ships are even higher.

Whichever way the industry moves, one thing is certain. It won’t be cheap. There are very different estimates from various sources on how much the extra costs for shipping would be, ranging from modest a $5 billion to $70 billion annually, which clearly shows how much uncertainty surrounds the whole issue.

And that is not just the shipping problem. Considering the sorry state of the freight market, shipowners will not be willing or able to absorb such massive extra costs themselves and will have to pass the lion’s share to their customers, who pay the freight. This would be people who trade the actual commodity. And the extra bunker fuel bill can be quite substantial, especially on long-haul voyages.

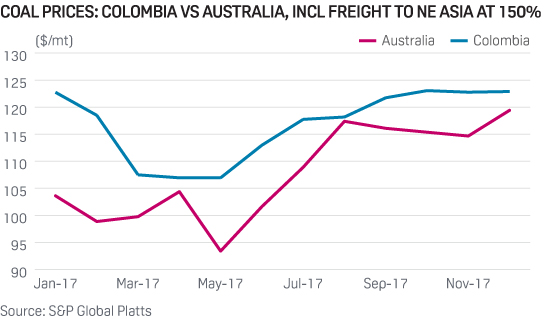

Let us look at a specific example – the coal arbitrage from Colombia to North East Asia. Obviously Columbia is not the biggest player when it comes to this region. Australia and Russia are as they are much closer to the buyers. However, in both 2016 and 2017, Colombia successfully took a considerable bite out of their market share, selling over 3 million mt /year of bituminous thermal coal to NE Asia.

The graph below compares the Australian and Colombian coal prices, including Panamax freight to NE Asia. For the sake of simplicity it is assumed that freight rates on both routes stayed constant throughout the year.

Source: Platts

It is quite clear that there have been pockets of arbitrage from Colombia throughout the year, when the delivered price of their product was more competitive than that of Australian.

This was made possible by the lack of volatility in the depressed dry bulk freight market, and relatively low bunker prices, which allowed a remote supplier to be competitive. The picture is likely to be very different in 2020 once the new IMO sulfur cap comes into force.

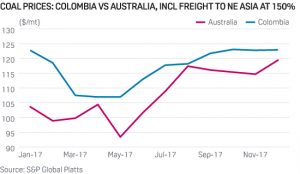

If MGO indeed becomes the go-to fuel for global shipping, the extra bunker expenses may skyrocket, making long-haul freight too expensive and an arbitrage like Colombia to NE Asia unworkable.

To put numbers in perspective, extra costs for one Panamax voyage on this route at current MGO prices, comparing to standard fuel oil would exceed $230,000. According to some estimates, the overwhelming demand for MGO come 2020 could propel its prices 2-3 times higher. Considering the trend for rising oil prices, the extra bill per voyage may easily come to half a million dollars, making the whole arbitrage of 3 million mt costing over $21 million more in just fuel expenses.

Since bunker expenses make up 70-80% of voyage expenses, the freight may easily double, especially on longer routes. However, as can be seen from the graph below, even at a modest 50% freight increase in freight, there would be almost no occasions when the Colombia-NE Asia arb would be workable.

Source: Platts

Certainly, depending on which side of the fence you are sitting on, it might be a good or a bad thing. In general, the further the seller is from his buyer, the more he will be exposed to the negative effects of rising bunker prices. At the same time their short-haul competitors might have a good excuse to smile wider.

Certainly, it won’t be just coal that will feel the impact of new regulations. The dry bulk market as a whole will be facing it. And since the same tonnage is often used across various dry bulk commodities, issues in one market may affect the other. For example, if the long-haul grain arbitrage from the Black Sea to the East was to suffer, a drop in ton-mile demand may ease the freight burden for US coal exports.

In time, of course, both the oil and shipping industries will readjust to the new realities and both the prices and trade routes will stabilize again. However, before that happens, players in the coal industry should start keeping a closer eye on what is happening with bunkers and shipping to avoid nasty surprises on their P&L sheets in the new decade.